My Research: Political Barriers to Solar PV in Florida – Results (1/3)

Note: This is Part 1 of a three-part series of blog posts that delve into the findings of my thesis research. Part 2 and 3 will be released over the course of next weeks and will feature a more close-up look at the policy barriers and explore strategies at the sub-state level to deploy more solar.

Summary of Results

When it comes to solar PV adoption, Florida has been called many names: laggard, slow-mover, a big disappointment or outright hostile. In 2016, these characterizations faced their first test as two ballot initiatives about solar rights/restrictions and solar system tax treatment battled for the hearts and minds of Floridians, who saw themselves tossed in the middle of solar advocates on the one side and the utility camp on the other. The two ballot initiatives shined a light on a couple of high-profile policies such as solar leasing, net metering, solar charges and tax exemptions that co-determine the incentives to deploy more solar in the state. Still, there are a range of equally, if not more, consequential policies that shape the investment incentives that feature less prominently in the public’s mind but warrant greater attention.

This research takes a more comprehensive view at policies and aims to disentangle Florida’s political barriers to solar PV, defined as any legislative or regulatory disincentives to deployment, and assesses their respective weights in slowing greater solar adoption. Second, it explores the underlying reasons for their existence and, third, identifies strategies sub-state actors such as counties and cities use to stimulate solar within the existing state-level policy framework.

Overall interviewee breakdown by sector (n=19)

In this endeavor, the theoretical and empirical literature on barriers to renewables provides a scaffold for a total of 19 semi-structured expert interviews with industry experts, and county-and city-level officials representing both sides of the argument. The interviewees provided their assessment of the biggest political obstacles and reasons underlying them, which are then presented in aggregate alongside the findings distilled from secondary research. County-and city-officials provided best practices in incentivizing deployment at their level of government.

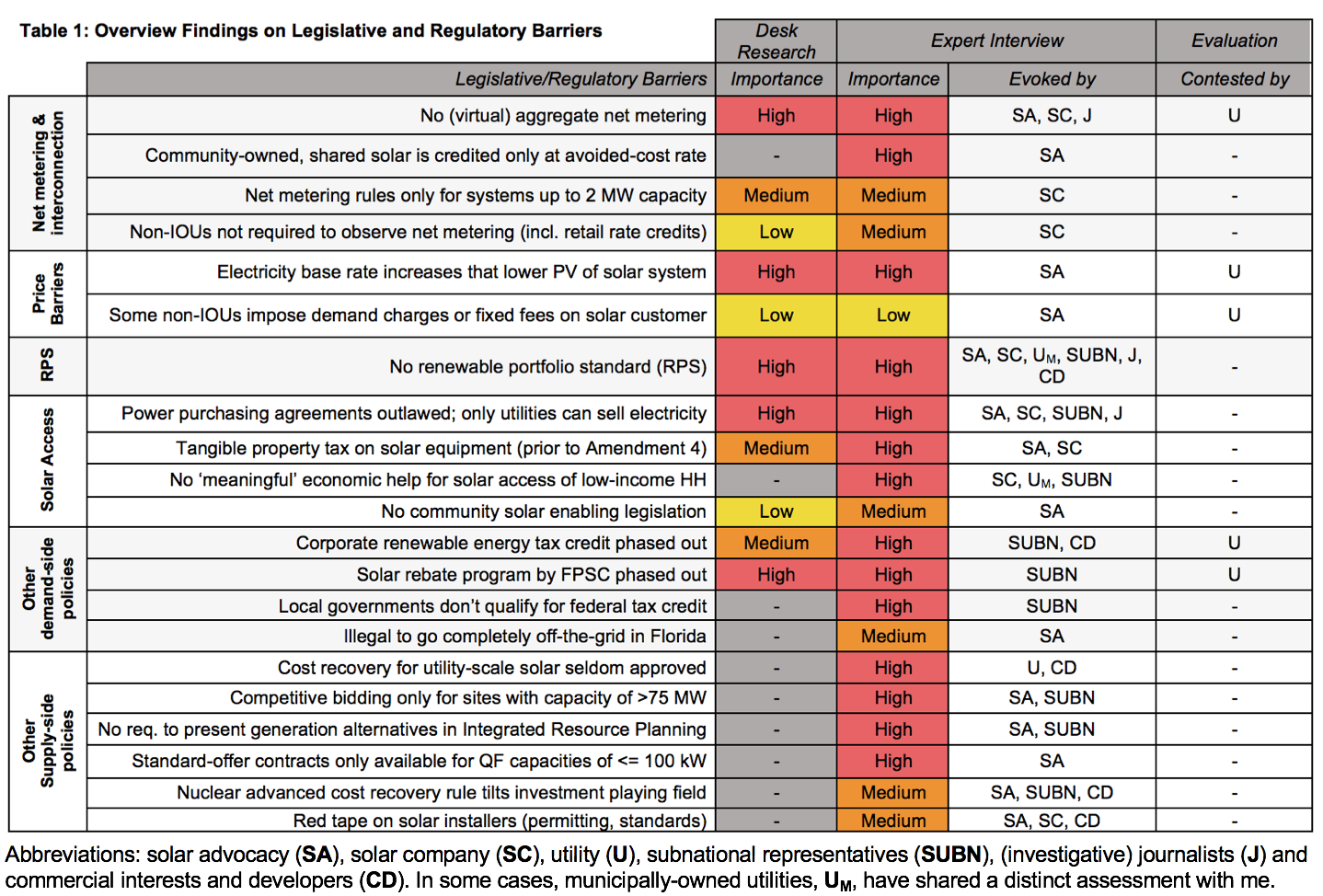

When it comes to high-impact policy barriers, the greatest level of agreement among interviewees was about the failure to get a renewable portfolio standard implemented. This is perceived to be compounded by the regulatory ban on third-party providers, who are barred from entering in power purchase agreements with residential and commercial customers. Further, the absence of virtual net metering as a cornerstone of community-owned solar and the fact that shared solar is compensated only at the avoided-cost rate are cited as first-rate impediments to more distributed solar. Utility-scale solar, which according to utilities themselves, is cost competitive in certain regions is said to be held back foremost by the multifaceted market insulation of utilities as well as the regulatory failure to mandate that utilities consider non-fossil fuel generation alternatives in their resource planning.

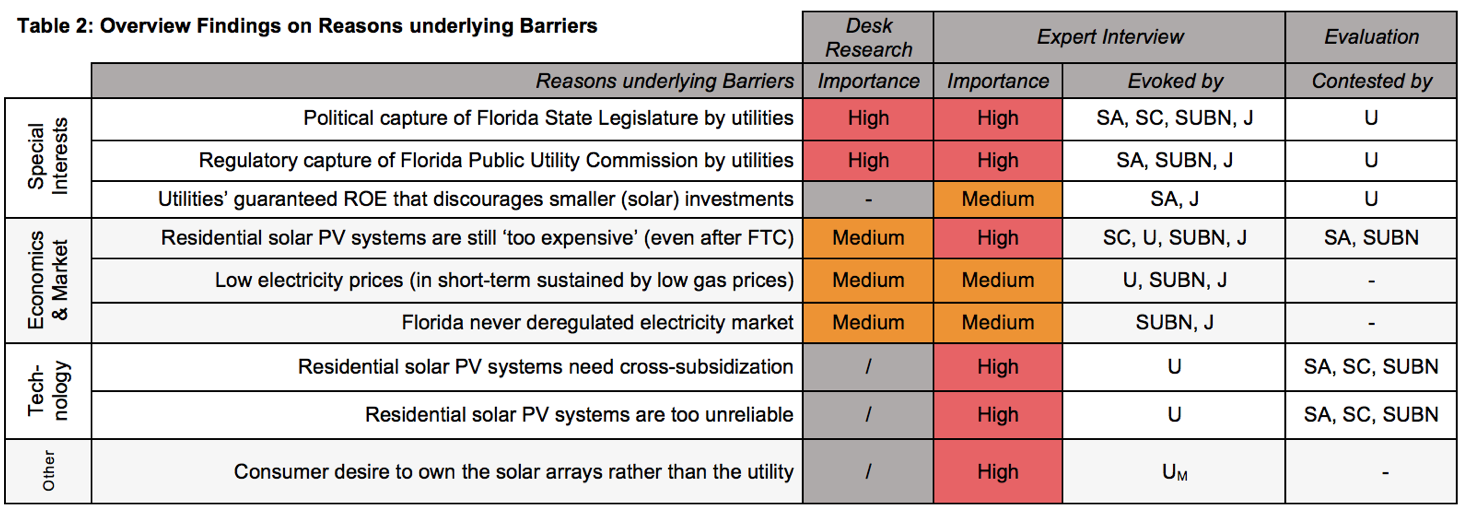

With the exception of utility representatives and affiliated groups, there was consensus that the political and regulatory capture by fossil fuel interests lies at the core of these disincentives. Campaign-sponsoring and donations to both political parties maintain a dependency between the majority of legislators, who select the industry’s regulators. In absence of support for low-to-middle income households, the difficulties to monetize the 30% federal solar tax credit restricts the income segments for whom investments in solar systems pay off quickly.

Mirroring great regional differences in Florida, in terms of renewable energy support and adoption, some counties and cities have backed proven financing models and partnered with solar cooperatives to reduce the upfront cost of solar. Even as Florida can legitimately be called a solar laggard at this point in time, there is ample space for sub-state actors to further reduce soft costs of solar and build on early successes in policy coordination on lower levels of government.

Check in next week for Part 2, which will look in more depth at the individual policy barriers and reasons for their existence. Also be sure to catch up on an earlier post, where I introduced a fully interactive map of Florida’s behind the meter solar capacity county and utility from 2005 onwards.