Municipal Collaboration on Coastal Climate Change Adaptation

Picture Credits (all Flickr, occ. cropped, left to right): Jasperdo, Doug Kerr, Robert Linsdell, cmh2315fl, massmat , Jennifer Macaulay, Tom Whitten

Constraints and Opportunities for North and South Shore municipalities in Massachusetts

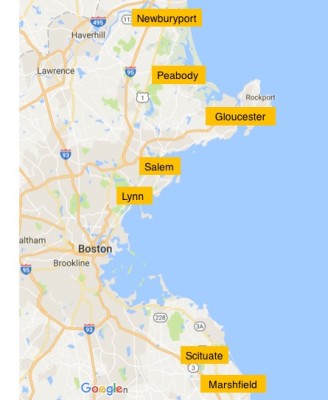

This research looks at coastal adaptation capacity constraints and collaboration opportunities of Massachusetts coastal municipalities from Newburyport in the north and Marshfield in the south (see right for map of included municipalities). Thematically, it is concerned foremost with the effects of both sea level rise and extreme weather events on coastal infrastructure and ecosystems in the region. Building on 21 conversations with municipality representatives, nongovernment conservation groups, Commonwealth departments and agencies and many more, it sets out to answer the following three questions:

- What are the greatest constraints at the municipal level to implement coastal adaptation strategies?

- Is there potential for greater inter-municipal collaboration on adaptation? If yes, on which issues?

- Which stakeholders should be included to in these collaborations?

Introduction

For longtime residents of the Massachusetts coastline the events of 1978, 1991 and 2007 are carved into their collective memory. Locals recount how the Blizzard of 1978, the “Perfect Storm” of 1991 and the particularly severe Nor’easter of 2007 inundated the coastlines, left flooded properties, irrevocably damaged infrastructure and disrupted ecosystems in its trail. There is ample scientific evidence that the frequency of such severe weather events will increase as the atmosphere continues to warm, but for residents of the Massachusetts shoreline this predicament is compounded by the slow-onset threat of sea level rise. Official estimates project that on average the Commonwealth is on track to experience sea level rise of 20-44 cm (8-17 in) by 2050 and two to five times as much in 2100.

On a regional level, the Regional Planning Agencies, in particular the Metropolitan Area Planning Comission (MAPC) that encompasses Greater Boston, are at the forefront of implementing the short to medium term strategies set out originally in the Massachusetts Climate Change Adaptation Report. Driven by a populace that has one of the highest shares of people believing they are personally affected by global warming, the Governor of Massachusetts signed an Executive Order in late 2016, which forsees among others, the crafting of a statewide adaptation strategy and a technical, adaptation assistance program to all cities and towns. Communities located along the North Shore, such as Newburyport, Salem and Gloucester and those located south of Boston, Marshfield, Duxbury and Scituate, have already recognized the need to integrate the latest climate projections into vulnerability assessments, updated floodmaps and sea level rise studies.

The highly context-specific nature of coastal adaptation measures provides opportunities for cost-effective collaborations among neighboring municipalities or those with similar risk profiles. The Metropolitan Mayors Coalition or the North Shore Task Force under the auspices of MAPC are emerging fora in which city officials can bundle their respective expertise and determine priorities. The bulk of the existing literature on municipal climate adaptation, which might provide clues about how to best design municipal climate collaborations, has traditionally focused on large cities. More recently, a few notable exceptions are beginning to investigate the specific challenges smaller, New England towns face in confronting higher flood-risks.

This research aims to contribute to this emerging body of work and seeks to build upon the suggestion in previous research to involve stakeholders beyond city planners in the quest to diagnose critical, municipal resources for coastal adaptation and venues for greater collaboration. These issues are particularly timely and could inform the design of Massachusetts technical, adaptation assistance program and ongoing work by MAPC on a tool that helps towns assess their vulnerability to climate change.

Findings

1. Greatest constraints at municipal level:

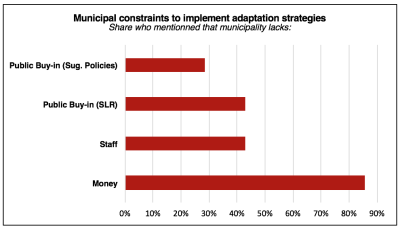

In the eyes of the local officials interviewed, there are four significant barriers to implement coastal adaptation strategies, which they deem necessary to protect their municipality from sea level rise and storm surges.

Foremost, the planners are concerned that the large-scale flood mitigation projects warranted in multiple municipalities fiscally overburden already cash-strapped municipalities. According to one town planner, a planned uppr-watershed stormwater drain system overhaul easily consumes 10% of the town budget. Another interviewee recounts that the costs for a capital improvement project of a critical water supply dam and spillway, directly affected by sea level rise, “scared” the council members so much that they only budgeted in increments for the first stages of the project.

Municipalities try to draw on external funding sources such as coastal resilience grants from the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, FEMA grants or federal support in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. However, there is some frustration about the tight eligibility requirements and long bureaucratic process particularly for FEMA grants. Despite significant outreach efforts by the RPAs and nonprofit organizations such as TNC Mass and Mass River Alliance, less than 10 municipalities across Massachusetts authorized or adopted a financing mechanism known as stormwater utility.

Three out of the seven interviewees note that they do not have enough staff capacity to deal comprehensively with the coastal adaptation demands. In practice this often means that most city or town administrations don’t have a staff member that works exclusively on climate change adaptation projects. Expecting the adaptation challenges to mount in the future; 60% of the municipalities consider themselves understaffed to meet emerging demands.

From the perspective of town planners, the third major constraint on implementing adaptation strategies is insufficient buy-in by local residents and businesses, who – in three out of seven cases – are not fully convinced yet that sea level rise actually occurs and/or poses a significant threat to their locality. In two municipalities there is considerable pushback to buy-outs of severe repetitive loss objects, residential property restrictions or anything that could imperil ongoing waterfront developments.

Speaking mostly anonymously on this sensitive matter, several interviewees outside of towns strike more critical tones. They lament that so far political leadership at the regional and local level is absent. If coastal adaptation were made a political priority and officials were realizing that co-benefits from climate adaptation could be reaped and mustered for election campaigns today, then, they say, financial resources and staff capacity could be found. The unwillingness to raise revenue or back innovative work is seen as a direct consequence of adaptation work losing out against other interests and priorities.

2. Potential for greater inter-municipal collaboration:

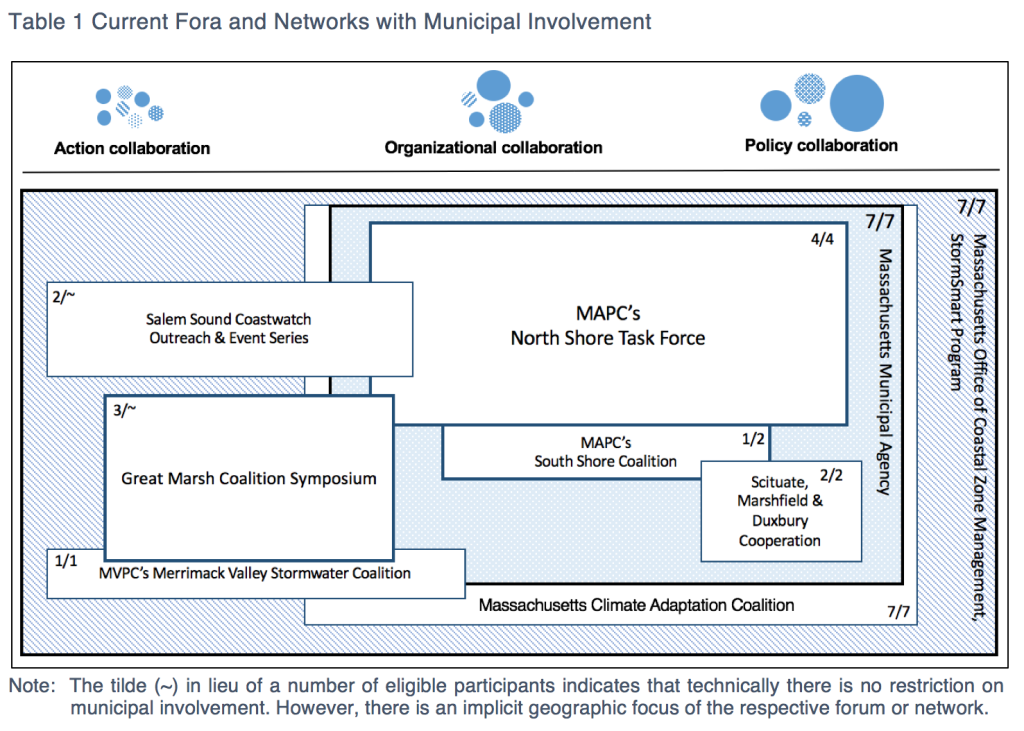

There are a host of different fora or networks in which representatives of municipalities have a chance to exchange best practices, receive technical training and coordinate unilateral or joint efforts to address hazards created by sea level rise. Adopting the collaboration typology introduced before, Table 1 structures the existing forums and networks covering issues related to coastal flooding in which the municipalities are reportedly involved in. Every box designates a network or forum dealing fully or in part with coastal climate adaptation issues with participation of at least one of the seven surveyed municipalities. The numbers in the corners of the boxes indicate the share of the eligible municipalities under study represented in the respective network or forum. Geographic restrictions on participants apply, for example in the case of the Merrimack Valley Stormwater Coalition and only one municipality under study is eligible for membership. The degree of overlap of two boxes signals the number of municipalities represented in both fora or networks.

Currently, the two most important policy and organizational collaborations, according to the interviewees, are the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management (CZM) StormSmart initiative and the subregional committees of the Metropolitan Area Planning Commission (MAPC).

CZM’s StormSmart provides technical assistance, resiliency grant funding and educational material to all coastal communities since 2008 and has been praised by many of the interviewed planners for the vital guidance and financial support it provides. Resiliency grant recipients are asked to take the transferability of a project’s “approach, technique, and products” to other municipalities into account. Dedicated CZM liaison staff interacts with the municipalities on a one-on-one basis, but there is no formal roundtable that includes multiple municipalities anymore. This function is taken on mainly by MAPC’s subregional committees, which both meet once per month in a large round table and discuss topics of regional relevance that span juridictions such restoration partnerships or FEMA’s Community Rating System.

Besides, there are a number of more local/regional networks with strong nonprofit participation that can classified as action and organizational collaborations. For instance, Salem Sound Coastwatch and the Great Marsh Coalition take on leading roles in educating town officials and the interested public about the effects of sea level rise on critical habitats and communities as well as spreading the word about financing mechanisms. The Massachusetts Climate Adaptation Coalition, a lose consortium of more than 40 state agencies, local government networks, nonprofits and businesses, works primarily through legislative advocacy, but also maintains a public outreach function. More recently, the Massachusetts Municipal Association, which brings together municipal officials from across the state, has taken a more active interest in stormwater management and used its annual meeting as a platform for policy dialogue. Descriptions of the remaining networks can be found in the Appendix of the full report.

The 23 conversations that inform this research uncovered a number of areas for greater inter-municipal collaboration. Multiple interviewees highlight that collaboration on the level of MAPC and CZM would be more effective if municipalities were further grouped by specific needs (grouping communities engaged in constituent outreach for resiliency plans fore example) and more priority were given to helping communities (individually & jointly) access state funds. The interviewees further underscore the persistent need to build on recent successes in constituent outreach on the scientific evidence for sea level rise and the need for (often unpopular) policy responses. Closely intertwined, it is recognized that local officials and regional planning agencies need to step up leadership when it comes to translating existing analyses into much more politically difficult adaptation action.

3. Suggested collaborations and stakeholders to be included:

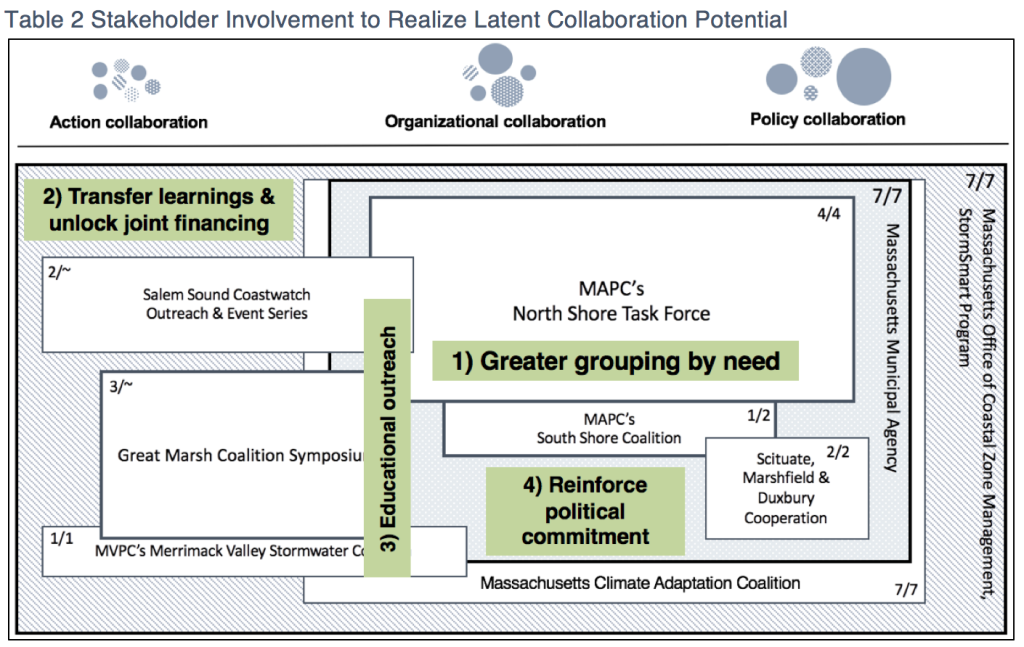

Table 2 takes the collaboration typologies and associated obstacles from Section 6 into account and depicts which stakeholder constellations lend themselves best to realize the latent collaboration potential that the interviewees identified.

1) The subregional committees of the MAPC provide established, inclusive and well-functioning fora in which participating municipalities can split up into smaller, more thematically tailored groups during their monthly meeting to discuss pertinent issues of the day. This could increase the pressure to act, especially in early stages of implementing adaptation projects as it facilitates better peer-to-peer comparisons among municipalities.

2) CZM houses the greatest subject matter expertise and enjoys unrivalled trust among planners. By dedicating more time to helping municipalities navigate different funding resources and making learnings from resiliency grant projects available online, they could become an even more coveted partner for resource-scarce municipalities, which tend to get stalled in the direction-setting and implementation stages of projects. Such assistance would also contribute to alleviate the funding constraints outlined by interviewees.

3) Salem Sound Coastwatch, the Great Marsh Coalition Symposium, MVPC’s Stormwater Coalition and the Massachusetts Climate Adaptation Coalition each have established channels for public outreach to distinct target audiences. Salem Sound Coastwatch and the Great Marsh Coalition are deeply rooted in their regions and can vouch with their reputation for broader environmental preservation and restoration for the credibility of sea level rise. MVPC’s Stormwater Coalition and the Massachusetts Climate Adaptation Coalition are better suited to educate town officials and state legislators about the urgency of climate adaptation support.

4) The Annual Meeting of the Massachusetts Municipal Agency offers a high-level meeting in which climate adaptation can be pushed further up the agenda propelling municipalities through the problem-setting stage. In a best case scenario, widely communicated adaptation projects successes with political returns can foster a social norm, which gradually reinforces extant political commitment for coastal climate adaptation.

Full report

If you would like to read the full paper, which includes a in-depth coverage of different collaboration typologies, a discussion of the private and public goods nature of different adaptation strategies, a conclusion with next steps and appendices, please send me an email via email: n.d.gunkel@lse.ac.uk.