Climate Forensics: “Little Ice Age” in Dutch Landscape Painting

Earlier this week I decided that I could no longer postpone re-visiting one of my most cherished art museums in Berlin – the Gemäldegalerie (Picture Galerie), which houses one of the most comprehensive and discreetly curated collections of Dutch genre and landscape painting of the 17th century (the Google Arts&Culture Project actually allows you to get as close to the canvases of Jacob van Ruisdael, Jan Vermeer and Rembrandt as no museum guardian would ever let you).

To drown out the ear-piercing squealing of the underground on my way to Potsdamer Platz, I listened to my favourite climate science podcast “Warm Regards” – the irony of it in a crowded, sticky wagon with what felt like 95°F didn’t escape me. In this specific episode on climate forensics co-host Jacquelyn Gill provided a glimpse into the toolbox that paleoecologoists like herself, and other climate scientists, use to reconstruct changes to the ecosystem and the prevailing climatic conditions over large stretches of time.

At the entrance to the collection, I switched from my iPhone to the museum’s audioguide and was not expecting to be reminded of climatological archives, sediment cores, and pollen samples again. As I roamed through the rooms I soon rediscovered Aert van der Neert’s “Winter Landscape with Ice Skaters at Sunset” (ca. 1655-1660), which made a lasting impression on me the last time I saw it a couple of years ago. The painting shows jolly Dutch townsfolk skating (and wobbling) over a frozen canal set against the backdrop of a softly illuminated sky, with its yellow sun faintly receding against the mounting evening clouds.

But then the audioguide explained that for people living in 17th century Holland the sight of frozen canals, people playing kolf (variant of golf, but on ice), and children racing underneath the bridges, like in Amsterdam in 2012, wasn’t such a once -in-a-decade spectacle as it was during most of the last century and nowadays. Paintings, like the winter landscape by van der Neer, could thus be treated as windows into the past for researchers. One prime question that arises in such investigations is whether information about climatic conditions at the time can be deduced from the depictions of nature and if yes, whether these can complement more traditional proxy data from ice cores or observations of sunspots.

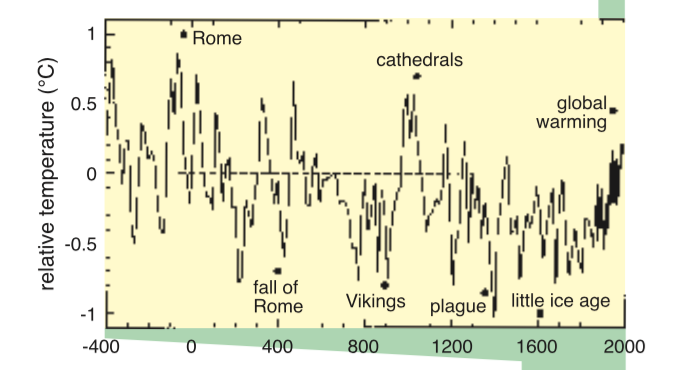

In 1970, American meteorologist Hans Neuberger published a study of more than 12,000 paintings he had surveyed covering continental European and later US-American paintings originating from 1400 to mid-20th century. Neuberger categorized these paintings along various dimensions with cloudiness and blueness of the sky among them. Today, there are quite strong concerns among scientists about the validity of some of the conclusions he reached. There appears to be a consensus that the period in which near to natural depictions of harsher climatic conditions appeared more frequently coincided with an era called the “Little Ice Age” (LIA) by meteorologists. They generally tend to date the LIA from 1500-1800, peaking in the mid-17th century, a period of cooling in large swathes of the Northern Hemisphere that followed the Medieval Climatic Optimum.

Course of Greenland ice core measured temperatures; from: Muller and McDonald (2000): Ice Ages and astronomical causes

Currently, most scientists agree that the causes of the cooling lay in a combination of volcanic eruptions, reduced solar radiation, changes to ocean circulation, as well as long-term changes to the Earth’s orbit. As a consequence of the cooling, it has been shown that the Haarlem-Leiden canal in Holland was frozen for an average of 28 days (SD: 25 days) in the 17th century. The researchers from the GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam elaborated on the freezing canals and changing skies in their study of the LIA and Dutch landscape painting. They also pointed to the prominence of windswept trees in paintings, such as Solomon van Ruysdael’s landscape piece below, as indication that higher wind speeds likely accompanied the cooling period and ultimately shaped the paintings we see today.